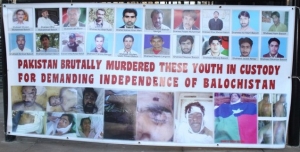

Kill and dump

Even as the families move on in the hope that they will meet their loved ones with the passage of time, there seems to be no end to the stress they go through on a daily basis.

Two days before Eidul Azha, nine mutilated bodies were found near the outskirts of Turbat district of Balochistan. About 10 were found dumped near Khuzdar.

“Whenever a body is recovered from any area, my mother gets ill,” says Farzana Majeed Baloch, sister of Zakir Majeed, who went missing a few months after Reiki in 2009. “She thinks that it might be him.”

Speaking about the atmosphere at home since Zakir went missing, Farzana says that it is “worst, but we still hope that he comes back”.

Majeed, who was the senior vice chairman of the Baloch Student Organization (BSO), was whisked away by unknown men from Mastung.

Within the span of two years, many people who had gone missing from Balochistan have either been found dead or there is no clue whatsoever where they might be.

Looking at the recent trend of “kill and dump”, Qadir says that there is little hope that people who have gone missing will come back home alive.

Recalling some recent instances, he says that at times the families just received a bag full of ears, fingers or arms, and they were asked to recognise their family members as there was nothing else available.

Farzana has been going from commission to commission to convey just one message — her brother is “not against Pakistan” — and says if Zakir has done something let it be decided in a court of law.

Zohra Yusuf of the HRCP says that the recent trend of killing people and damaging their body parts is going to “create another generation of hatred”.

Although human rights organisations have been really forthcoming in highlighting the cases of missing persons, there have been times when their own workers were abducted while researching on cases of missing persons.

“They were let free a few days back though. But now we do our job as discreetly as we can,” says Abdul Hayee, a field worker from the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP).

Families turning into activists

After waiting for six years for her husband, Masood Janjua, to return, Amna Janjua was recently informed through an affidavit submitted in the Supreme Court that her husband was dead and not with the intelligence agencies.

“This happens when state itself is against someone,” she says and adds that she is not willing to accept what is written in the affidavit.

Janjua still believes that her husband is in detention somewhere. A mother of three, Janjua has come a long way in finding her husband and feels she is too determined to go back now.

From crying endlessly after knowing about her husband’s disappearance to fighting and protesting with other families against the enforced disappearances of many, Janjua says she will sacrifice her whole life for the cause.

With the help of people like Amna Janjua and Qadir Baloch, who is the head of the Voice for Baloch Missing Persons, people with similar stories now have a shoulder to lean on.

Threats and insecurity

Families have a lot of complaints against the judicial commission. At the same time, families of the missing fear speaking to the commission members in the presence of “unknown people”, says Zohra Yusuf.

The first session of the commission was held in Quetta. But later on, the head of the judicial commission, Fazlur Rehman, was transferred to the Election Commission of Pakistan. That delayed a lot of meetings that the families waited to have with the commission.

Travelling to either Quetta or Islamabad from far-off districts or cities also becomes a problem for them with almost zilch financial prospects. Besides, there are constant threats to stop pursuing the cases of their family members.

“You cannot trust anyone besides your family,” says Farzana. She usually waits for her brother to pick the phone calls or does not pick it at all.

At present, there is police protection provided to Janjua, but even then she gets at times veiled or direct threats to “stop maligning the government”.

“I know it is to depress me or to scare me off, but I won’t,” she says adamantly.

Crisis management cell

The sitting head of the Crisis Management Cell refrained to give complete statistics on the number of people that went missing. And he has a reason to do so.

Farid Khan of the Crisis Management Cell, Islamabad, says that the number of missing people is overshadowed by the number of abductions that occur simultaneously, which makes it a “complex issue” to speak on.

Speaking about the number of registered cases with the commission, Khan says that there are 264 cases of now. “Apart from that we have traced 500 people within a few months.”

Despite the fact that forced disappearances have become a known phenomenon in the country, no institution is willing to accept responsibility. Confusion still prevails over who is actually behind these abductions and killings.

“You can compensate the losses of flood victims. But how can you compensate our loss. If only the state could understand our plight,” says Janjua.caption

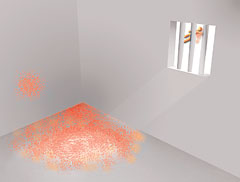

Illustration by Faraz Maqbool

http://www.thenews.com.pk/TodaysPrintDetail.aspx?ID=81145&Cat=4&dt=12%2F8%2F2011#.TuAIrfGNiM1.facebook