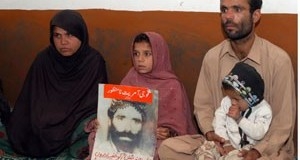

Bilal Mengal was an honorary journalist in Nushki, with nine children to feed, who on a Colonel’s offer became a uniform-making contractor at the army’s Nushki Fort. He did not know it would cost him his favourite son Khalid who he took with him to help stitch.

The standing orders at the fort were no officer or soldier could go out without express permission due to the danger of attacks. One day, Naib Subedar Ramzan violated orders and was injured in firing. The incident occurred at 6:15 and Bilal left the fort at 7:30 but was arrested for the incident. The trial went on for 10 months, and one day other prisoners told him that his son Khalid was picked up. Khalid returned after 25 days but that was not the end of story; on the night of May 16, 2011, his house was raided and his sons Khalid and Murtaza were taken away. From the roof of his house he saw those vehicles enter the fort. Bilal asked the police station’s SHO to help, who followed until the gate but was turned back. He filed an FIR, and began a hunger strike, then filed a petition in the Balochistan High Court (BHC). He managed to wrangle a meeting with the PSO of Quetta’s Corps Commander, which ended in confusion as instead of being helped, was told that he, Bilal, was sentenced to 25 years and should be in jail. Bilal appeared in the Supreme Court hearings initiated by the Chief Justice but did not seem to have much faith. “The Chief Justice comes here only to keep up appearances. He is only concerned about saving his own face. Nothing has changed, nothing will change.” Khalid is still missing.

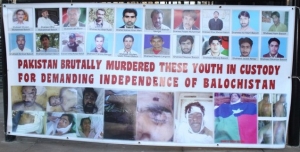

Farzana Majeed, elder sister of the missing Zakir Majeed, represents the new face and phase of the Baloch struggle. Never before have Baloch women participated so actively and extensively; state atrocities have forced them into this role. Farzana has done her Masters in Biochemistry from Balochistan University and is enrolled in the M Phil programme. But instead of attending classes and working in a laboratory, she sits at protest camps demanding the release of her brother. Zakir was the vice president of the Baloch Students Organisation (Azad), a nationalist students organization, and a student of Masters in English. He was returning from Mastung with friends when they were apprehended by intelligence personnel. His friends were released soon and they informed Farzana; TV channels too carried the news. Zakir’s brother filed an FIR in Mastung. Farzana was worried about their ailing mother but had to eventually tell her; the lady broke down and started praying and is still praying.

Farzana filed a writ petition in the BHC, and she has since joined protest camps everywhere, hoping to highlight her brother’s disappearance. She camped at Islamabad with Mama Qadeer and met Justice Javaid Iqbal who told her what he has told every other Baloch family: shut down the protest camp, go home and your family members will be with you within a week. Hanif says, “Javaid Iqbal has played a curious role in perpetuating this nightmare. He has made so many false promises to so many families that many see him as part of the problem.”

Farzana returned to her hometown Khuzdar and started receiving calls that Zakir would never return. Then the bodies of Zakir’s missing comrades began cropping up at regular intervals. They found Ghaffar Lango’s body, then Sameer Rind, Jalil Reiki, Sana Sangat’s body, which had 28 bullets in it. For two years, they kept getting news about him but a year and a half ago that stopped. Farzana has given up on the Pakistani state and its people. She says. “Isn’t it quite obvious that they hate us Baloch people? If Zakir has committed a crime, why don’t they bring him to a court, put him on trial, and punish him? Why are they punishing the whole family, the whole nation?” At the protest camps, she spends her time reading books about revolutionaries and politics like Che Guevara’s biography, Spartacus and Musa Se Marx Tak to learn about revolutions and other peoples’ struggles.

(To be continued tomorrow)

The writer has an association with the Baloch rights movement going back to the early 1970s. He tweets at mmatalpur and can be contacted at mmatalpur@gmail.com