Indeed, ‘missing persons’ is a misnomer- a more pertinent term would be ‘enforced disappearances to sow seeds of terror in a recalcitrant populace.’ The reason for this term is simple: involuntary disappearances lead to flagrant violation of human rights as well as due procedures of law for detaining, imprisoning and investigating a person for an alleged crime. An act of involuntary disappearance and arbitrary detention violates the constitutional rights to liberty and security of person and safeguards against arrest and detention. Article 9 of the 1973 constitution provides: “ No person shall be deprived of life or liberty save in accordance with law.” Similarly, article 10 of the constitution provides safeguards against arrest and detention, that is, provision of a legal counselor, and production of the detainee before magistrate within 24 hours of detention, and the only exception for the applicability of safeguards is ‘preventive detention’- and it is not again not for a prolonged period of time but the case of the arrested person is liable to be reviewed after three months by a Review board[ii].

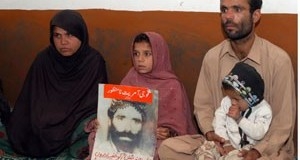

Human rights organizations and activists in Pakistan have voiced concern over the incidence of ‘missing person’ in Baluchistan, and have held the security and intelligence agencies responsible for disappearances[iii]. A Human Rights Watch report has given elaborate evidence from “released detainees and their relatives, and witness descriptions of abductions, indicating the involvement of intelligence agencies in the disappearances. According to the same report, in certain instances, “government officials have admitted state responsibility; in a few cases, representatives of the intelligence agencies have admitted responsibility to families or during court hearings”[iv].

The cases of ‘missing persons’ have been sporadically reported in 1990s in the context of military operation in Karachi; but the incidence of enforced disappearances assumed alarming proportions in the backdrop of Pakistan’s partnership with the USA on the war against terrorism. A number of suspected terrorists, including doctors, computer experts and students, were hauled in by the intelligence agencies and handed over to the US intelligence agencies. But their cases did not elicit public sympathy because of their alleged linkages with the terrorist organization[v].

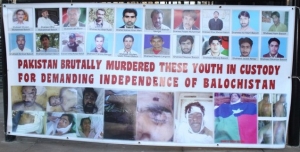

However, in Balucistan, a low key insurgency, fuelled by the federal government’s economic decisions regarding Baluchistan such as control of local mineral and fossil fuel resources and construction of the Gwadar deep-sea port, and the presence of armed forces and troops of Frontier Corps(FC), increased in momentum after the killing of Nawab Akbar Bugti in a military operation and many nationalist organizations began attacking non-Baluch civilians and security personnel. To contain the growing insurgency, activists of Baloch nationalist parties and movements, including the Baloch Republican Party (BRP), Baloch National Front (BNF), Baloch National Movement (BNM) and Balochistan National Party (BNP), as well as the Baloch Student Organization (Azad), or (BSO-Azad), were abducted and shifted to secret detention centers for investigation by FC and intelligence agencies In some cases, people were purportedly targeted on account of their affiliation with a particular tribe, such as the Bugti or Mengal, who were fighting with Pakistan’s armed forces[vi].

The number of missing persons ranges from tens of thousands to a mere few hundred. As the circumstances surrounding the involuntary disappearance of people from Baluchistan are shrouded in mystery, so the exact data on the missing persons is not available. Muhamed Hanif, a renowned journalist and novelist, who has authored a pamphlet on missing persons in Baluchistan, writes in the pamphlet:

“There are thousands missing if you believe the Baloch Nationalists, hundreds according to the human rights organisations and none according to our intelligence agencies”[vii].

Despite confusion about numbers, after the documentation of cases of missing persons by the human rights organizations and the staging of protest demonstrations by the relatives of disappeared persons, Supreme Court of Pakistan set up two Commissions in 2010 and 2011. The mandate of both commissions has been large, ranging from tracing the missing persons to apportioning of the responsibility for enforced disappearance on the state agencies. However, their success has at best been limited. Neither the Commissions have been able to trace registered cases of missing persons nor have they unequivocally established culpability of any state agency in involuntary disappearances. A number of reasons could be cited for the partial success of the Commissions. First, there are no witness protection mechanisms in place, and relatives are often required to give information at the Commission in front of representatives of the same agencies they accuse of involvement in the disappearances of their loved ones[viii]. Secondly, the legal domain and the operational accountability of the intelligence agencies could not be established before the Commissions. But on a positive side, the judicial review has kept the media attention on the issue of missing persons.

No doubt, the issue of enforced disappearances of persons in Baluchistan is not an easy task and requires strong political commitment on part of both the federal and provincial governments. Once the federal and provincial governments commit to tackle the issue of missing persons, a number of steps can be taken . First, an attempt must be made to account for disappeared persons by giving their relatives protection for reporting the case. Second, as the security agencies invoke laws such as the Security of Pakistan Act 1952, Pakistan Army Act 1952, Defence of Pakistan Act and Prevention of Anti-National Activities Act 1972 to justify their actions; so, the exact legal domain of the state agencies for arresting and detaining the persons must be specified.

Third, all individuals responsible for enforced disappearances, be they from police, FC or intelligence agencies, must be identified and made accountable for their actions.[ix] Finally, the operations of intelligence agencies must have civilian oversight. Regarding the role of intelligence agencies, Judicial Commission 2010 has aptly noted:

That a body of state functionaries is not subject to its writ is a matter to be settled by the state. The citizens cannot be penalised for the state’s incompetence and inadequacies[x].

Unless some corrective measures are taken, the continuous state of exception and the ensuing brutalization would further erode trust of populace of Baluchistan in the state of Pakistan.

References:

Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Giorgio Agambe, Stanford University Press: Stanford California, 1998, p-10.

[ii] Article 10 of Constitution of Pakistan ,1973.

[iii] Human Rights Commission of Pakistan 2009

[iv]‘ We can torture, kill or keep you for years’ Enforced disappearances by Pakistan forces in Baluchistan, Human Rights Watch 2011 accessed at http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/pakistan/document/papers/Weckill.pdf

[v] ‘The Baluch who is not missing and others who are,’ Mohamed Hanif, p-3, accessed at http://www.scribd.com/doc/127280475/The-Baloch-Who-is-Not-Missing-Others-Who-Are-By-Mohammed-Hanif

[vi] ‘We can torture, kill or keep you for years’ Enforced disappearances by Pakistan forces in Baluchistan, Human Rights Watch 2011 accessed at http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/pakistan/document/papers/Weckill.pdf

[vii] Looking for Uncle Ali, Muhammed Hanif, Issue V, tanqeed accessed at http://www.tanqeed.org/2013/08/looking-for-uncle-ali/

[viii] Amnesty International 2011, accessed at http://www.amnesty.ch/de/laender/asien-pazifik/pakistan/dok/2011/wo-hunderte-oder-tausende-verschwinden/DisappearancesPakistan.pdf

[ix] ibid.

[x] Ibid, p-7