They say their relatives were picked up by Pakistani security agencies and never heard from again. The marchers say they were repeatedly threatened by intelligence agents to stop their protest. At at one point during their 105-day march, a truck deliberately veered into them, injuring two women.

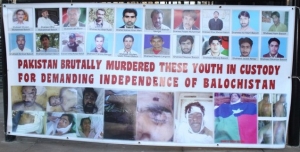

For the last decade, Pakistani soldiers have battled a separatist insurgency in the resource-rich province of Balochistan. Rights groups say thousands of Baloch have been detained by security forces, and only seem to turn up as dead bodies. Nearly 600 mutilated bodies of political activists and journalists have been found there in the last three years, according to the provincial government.

In January, three mass graves were discovered. Authorities say 13 bodies were found, but locals claim seeing more than 160. Three of the victims were identified as men picked up by security forces last year.

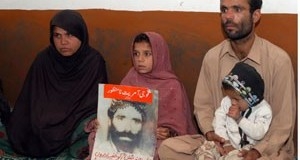

But more often than not, relatives of the disappeared simply have no idea what has happened to their missing loved ones.

Farzana Majid Baloch, one of the marchers, continues to seek her brother’s release, but says she really has no idea whether Zakir Majid Baloch is even alive.

“My brother was a political activist and the Chairman of the Baloch Students Organization,” she says. “I took part in many protests for him, his organization protested for him, even on the international level there were many protests, but the government is still not ready to release my brother.”

Like the other marchers, she has had no luck with Pakistan’s courts or government. The Supreme Court has found security forces to blame for the disappearances, but has been unable to force them to bring the Baloch in military custody into an open court.

“Along with the protests, I opened a criminal case for my brother’s abduction before the provincial high court, and before the Supreme Court. I attended more than 95 court hearings,” explains Farzana. “We have consistently asked that if my brother is guilty, bring him to a court and punish him there. This is no way to treat my mother, or myself, a sister who has lost everything trying to find her brother. If the government considers my brother to be a criminal, then bring him to court. But I have never gotten a response from the government.”

Mir Muhammad Ali Talpur, who fought in the last major Baloch insurgency in 1973, says the federal government has not learned any lessons from that period. The province still only receives a fraction of profits from its extensive mineral resources, and the military establishment refuses to acknowledge past abuses.

“Has anyone from the establishment been punished for the abuses it has committed against its own people?” asks Talpur. “If the Baloch asks for freedom, he is a criminal. Of course, his crime is asking for freedom, for his rights. In that case, I am a criminal, too.”

Former Baloch nationalists, including former leaders from the Baloch Students Organization, were elected into the provincial government last year, but they have been unable to solve the missing persons issue. Despite experiencing the first democratic transition in the country’s history, civilian leaders have failed to take the reigns of security operations from the Pakistani military.