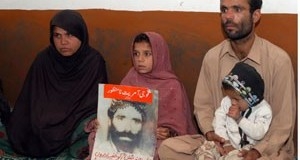

Hafiz Saeed was 25 when he disappeared. He was an obedient and bright son. He had done his Hifz-i-Quran by the age of 15. He went on to do his matric privately. He was teaching other children Hifz-i-Quran at Iqra School. He was the eldest in the family and was engaged to be married a year after he disappeared.

With his madressha background, his teaching job, his beard and his shalwar above his ankle, a lot of people, specially the security forces, tend to jump to the conclusion that Hafiz must have been somehow involved with some religious cult, some jihadi organisation. “He never did any of those things. After finishing his teaching work at school, he came straight to my shop in Gharib Abad and helped me out. He had cousins who were also madressah teachers. Sometimes they visited. I never heard anything political. He was very pious, yes, but he was a straight boy. He was the eldest of my children, he was close to me. I would have known.”

Hafiz Saeed didn’t return home that night. “My son had never not spent a night at home. I got worried. I started looking.”

Hafiz Saeed and his family had no personal enmity. His father assumed that Saeed had been picked up by the law-enforcing agencies for violating the curfew. He thought about kidnapping for ransom but told himself that who would expect a ransom from someone as poor as him. He registered an FIR, did the rounds of the hospitals and asked everyone he could.

“Fifteen days later a man came looking for me,” says Allah Baksh. “He came on a motorbike, introduced himelf as Yasin from MI.” Yasin from MI asked Allah Baksh if his son Hafiz Saeed was involved with any Jihadi organisation. “I told him that he wasn’t involved with anyone or anything except his teaching and my shop.” The man on the motorbike assured Allah Baksh that MI will investigate and if he was with any of the law-enforcing agencies, he’ll be released.” For next three months Allah Baksh kept looking but didn’t hear anything from anywhere. He filed a petition in the high court. The petition has been going on for eight years, now, but not once has he seen a glimpse of his son despite various orders by the court saying that a meeting should be arranged between the missing person and his family. He has not had any kind of contact with his son during this time.

In the intial hearing a statement submitted on behalf of the ISI said that Hafiz Saeed had been arrested after he was injured in the bomb blast and he was being interrogated. Crime Branch also confirmed in a separate report that Hafiz Saeed was in the custody of ‘sensitive agencies’. The high court instructed that a meeting be arranged with the family. The meeting never happened. Instead Crime Branch submitted another report, this time saying that Hafiz Saeed wasn’t in the custody of ‘sensitive agencies’.

Allah Baksh wrote letters to President, to Chief Justice but never heard back. For 11 months he sat in a protest camp outside Quetta Press Club. For all these years there was no sighting, no news of his son but he didn’t give up.

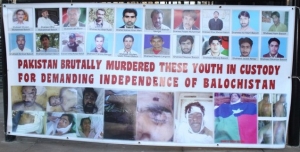

Then out of the blue a list surfaced in Quetta High Court in 2009. There were 13 missing people on it. They were all supposed to be serving time in jails. Hafiz Saeed was on it. According to the list he had been court martialled and sentenced to 25 years’ imprisonment. The report said that he was in Gujranwala jail.

Allah Baksh managed to contact HRCP who sent one of its people to Gujranwala jail. The jail authorities said they didn’t have Hafiz Saeed. Allah Bakhsh went back to the high court and this time police filed a submission that Hafiz Saeed had actually been killed in that blast and buried.

By now Hafiz Saeed had been suspected of being involved in the blast, suspected of being injured in the blast, and now six years later his family was being told that Hafiz Saeed had actually died in the blast. Allah Baksh reminded the court that his son had left home four hours after the blast happened. High court ordered a DNA test. Police were basically saying that one of the bodies that they had shown Allah Baksh six years ago was his son’s. “I had had a good look at those bodies,” Allah Baksh again gives a graphic description of the slit throat and decapitated legs. “That wasn’t my son.”

Before they exhumed the body that wasn’t his son’s, they gave him some clothes and asked if he recognised them. “These clothes didn’t belong to my son. After he became a Hafiz-i-Quran he never wore a shirt with buttons. But just to make sure I took these clothes to show his mother. And she also said that these were not his clothes.”

The body was exhumed and as Allah Baksh had predicted it wasn’t his son. He was relieved. But not for long. He says that secretly he envies people who have found the bodies of their loved-ones. “They have buried them and now they mourn them,” he says. “All I can do is wait.”

And while he waits, Allah Baksh can’t stop thinking of the events of that fateful evening. “What I don’t understand is that he came home after offering his maghrib prayers. There had already been a bomb blast. Then he took his bicycle and went out. There was curfew outside. I don’t know why he went out.”

Mohammed Hanif is an author and journalist. His pamphlet The Baloch Who Is Not Missing and Others Who Are is published by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan.