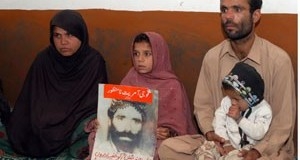

Farzana contacted the representative of the Human Rights Commission in Khuzdar. Her younger brother went to Mastung along with Zakir’s friends who were witnesses to his kidnapping and lodged an FIR.

Farzana kept making flimsy excuses to her mother about why Zakir hadn’t returned home. “Then a couple of days later she had to go out of the house to pay her condolences to a family friend. I realised that people will tell her. She’ll find out because everybody around us knew so I decided to tell her. I said casually that the police had taken Zakir.” Farzana’s mother broke down and started to pray.

“And she is still at it, she is still praying,” says Farzana, in an irritated tone, like someone who has serious doubts about whether anybody is listening to their prayers, that her mother’s prayers are as futile as her own protests, as useless as the court hearings she has been attending for the past four years.

Zakir had been arrested before for his political activities. Charges were always the same; organising a strike, a protest, at worst vandalism, etc. “Every time his case came up, the session judge freed him. There was no case against him. He was a political worker not a criminal.”

Two weeks after Zakir was kidnapped, Farzana filed a writ petition in the Balochistan High Court. Then she held a press conference in the Press Club in Khuzdar, staged a protest outside the Quetta Press Club and then in May 2010 set up a protest camp in Karachi, along with the families of other missing person. This was her first extended stay in Karachi. She stayed in various places while protesting, sometimes in Gulshan-e-Iqbal, sometimes in Lyari. She had been to Karachi as a teenager for sightseeing but this time around she herself was the centre of attention. “People occasionally dropped by to express their solidarity. The international media came. TV cameras came. But they didn’t really do much. Nothing changed. I even spent my Eid days in the protest camp. Nothing changed.”

Then suddenly disfigured bodies of the missing persons started to appear with greater frequency. Farzana along with Abdul Qadeer Baloch, a leader of the Voice for Missing Baloch Persons, who she refers to as Mama Qadeer, went and set up a protest camp in Islamabad in the hope of putting pressure on the authorities, to get the media to talk about the disappearances. Like every other family of the missing persons, Farazana went and met Justice Javaid Iqbal. Justice Javaid Iqbal told her what he has told every other Baloch family: Shut down the protest camp, go home and your family members will be with you within a week.

In his capacity as a former senior Supreme Court judge, and the man responsible for investigating the cases of the missing people, Javaid Iqbal has played a curious role in perpetuating this nightmare. He has made so many false promises to so many families that many see him as part of the problem.

They shifted the protest camp to Quetta and Farzana went home to Khuzdar to spend some time with her family. She started receiving anonymous, threatening phone calls. “Forget Zakir Majeed, he is never coming back.”

While she was still in Khuzdar, a fresh wave of killing and dumping of bodies started.

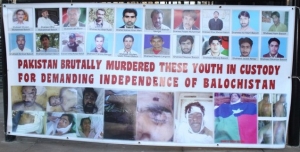

They found Ghaffar Lango’s body.

Lango, father of five daughters and a son, had been missing for three years. He was found near Gadani, his head full of wounds inflicted with a blunt weapon.

Then they found Sameer Rind’s body.

Rind was 24 and missing for a year. His sister had been campaigning along with Farzana.

Then Jalil Reiki’s body was dumped.

Jalil had been missing for two years. His father Qadeer Baloch had been organising all the protests.

Then Sana Sangat’s body was found.

Sana had been missing for three years. His body had 28 bullets in it.

All were Zakir Majeed’s comrades, all were killed after years of captivity. Their bodies told stories of unspeakable brutalities.

Farzana’s life is built around demanding an end to these stories.

Farzana changed her phone number, left Khuzdar and went back to the protest camp.

For the first two years, Farzana and her family kept getting messages from Zakir Majeed. She has a mental picture of her brother and his whereabouts. He is in a dungeon, with his other friends. “He was kept in Quli Camp. Other people who were kept in that camp and released brought us his messages,” says Farzana. But she hasn’t received any message for the last six or seven months. “He used to send us his love. He took the buttons off his shirt and sent us, to reassure us that he was alive.”

Farzana speaks without any bitterness, in a matter of fact way even when she is rattling off the names of her brother Zakir Majeed’s dead colleagues and the number of wounds on their bodies. But she gets angry when she talks about herself. “Look at me. I am 27 years old. Zakir is now 25. I want my life. I have my needs. What kind of life is this? I am spending all my life at protest camps in the hope that they’ll not kill my brother? What kind of life is this?”

She has given up on the state of Pakistan and its people. “Isn’t it quite obvious that they hate us Baloch people? If Zakir has committed a crime why don’t they bring him to a court, put him on trial, and punish him? Why are they punishing the whole family, the whole nation?”

How does she spend her time at the protest camps? “I read,” she says. “Books about politics. Books about revolutionaries. I have read Che Guevera’s biography. I have read Spartacus. I am currently reading Musa Se Marx Tak. I am learning. I am learning about revolutions and other people’s struggles.”

Mohammed Hanif’s pamphlet The Baloch Who is Not Missing and Other Who Are is published by Human Rights Commission of Pakistan.