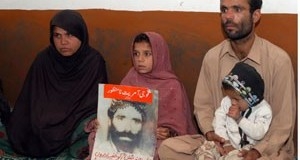

Saman has spent the last three years of her life in courts and protest camps, trying to convince the media to keep her father’s name alive in the news. She says, “I go to the court hearings but my heart is not in it; I know that I am not likely to get justice from these courts.” Her younger brother has had to leave school to work on the family lands to sustain the family.

Nasurullah Bungalzai, a former student of the Quetta Degree College, presently chairperson of the Voice of Baloch Missing Persons (VBMP), is in quest of his missing uncle, Ali Asghar Bangulzai, who ran a tailoring shop and was a political activist, a member of Khair Baksh Marri’s political party, Haq Tawar. He was picked up in 2000 but released after 14 days. During that period, Asghar was hung upside down in a well and asked to bear witness against Khair Bakhsh or the rope would be cut, but he refused. Nasrullah’s relentless campaign and his permanent protest camp outside the Quetta Press Club were becoming a bit of an embarrassment for the army establishment, so a Colonel Zafar of MI invited him for a meeting and asked him, “You have been meeting the governor?” He said he had at least seven times. The Colonel continued, “And you have been telling him to summon the local ISI commander to the Governor’s House?” He answered affirmatively. The Colonel said, “He can’t even summon my junior most captain here. He knows that and you should too.” Nasrullah, desperate to get a straight answer said, “Maybe you killed him and buried him somewhere inaccessible. Maybe you can’t take me to his grave,” and, “If that’s the case, then bring out the Quran, put your hand on it and tell me the truth. And I’ll leave you alone.” Colonel Zafar was not impressed by Nasrullah’s emotional appeals and said, “It’s no use. We are a machine. We are an emotionless machine.”

The second time Asghar Bangulzai was with his friend Iqbal when he was apprehended. Iqbal was brutally tortured but released after 24 days. In 2003, Nasrullah’s family managed to get a hearing with the Quetta Corps Commander, who for a change happened to be a Baloch, Abdul Qadir Zehri, and later was the governor too. But this proved fruitless. They sought the help of Hafiz Hussain Ahmad, the central leader of the JUI-F, and met Brigadier Siddique, the head of the ISI in Quetta. He said they had him in custody, and over a year they met him often but that too bore no fruit. They met General Zaki in Islamabad; help was promised but none came. Having lost hope in them, Nasrullah met Governor Owais Ghani again but was stunned when Ghani said, “If you continue your protests, I can’t guarantee your safety.” Nasrullah bitterly told him, “I am a common citizen. You are the governor. We are sitting in your Governor’s House and you are threatening me about my safety.” All wanted him to remove the protest camp and end their campaign, as it was giving them and the country ‘a bad name’. A high official from the interior ministry flew down to Quetta and met him. “He promised us that if we remove the protest camp, he’ll make sure that Ali Asghar would be released within two weeks.” Nasrullah consulted other families and the protest camp was temporarily closed down. Months passed, nothing happened, as they had been lied to. Ironically, it took nine years for even an FIR to be registered, and the Supreme Court and the government do not tire of praising their efforts for the Baloch.

When Ali Asghar disappeared, his oldest son was 12 and the youngest one only six months old. The oldest son got married a few years ago. After spending 11 years in search of his uncle, Nasrullah is frank about his own state of mind. “The whole family has psychological problems. I think we are all mentally sick.” In his absence, Ali Asghar has become a grandfather. His grandson also calls him chacha (paternal uncle) because Nasrullah refers to him as chacha.

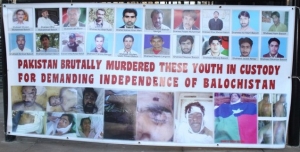

Disappearances are from across the entire spectrum of Baloch society and include intellectuals like Professor Saba Dashtyari; journalists like Lala Hameed Baloch and Ilyas Nazar; doctors like Dr Deen Mohammad and Akbar Marri; lawyers like Zaman Khan Marri and Ali Sher Kurd, and activists like Zakir Majeed and Sangat Sana. The Pakistani state is unforgiving and brutal in its treatment of the Baloch and it continues to deny responsibility by presenting flimsy excuses like people donning the Frontier Corps personnel’s uniforms to commit crimes. Such excuses simply expose its inability to run a state. The saga of the missing persons seemingly is set to continue and intensify as the Baloch, fed up with atrocities and denial of rights, are becoming more actively and openly defiant of the state and demanding freedom.

The writer has an association with the Baloch rights movement going back to the early 1970s. He tweets at mmatalpur and can be contacted at mmatalpur@gmail.com