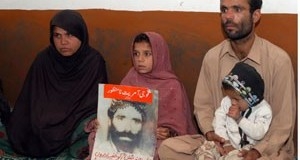

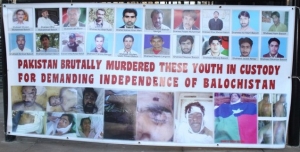

Since Pakistan’s independence, ethnic Baloch separatists have launched a series of armed uprisings against the central Pakistani government, which has often responded harshly. Groups such as Amnesty International have frequently denounced what they describe as forced disappearances and “kill and dump” policies directed against the Baloch.

In its 2013 annual report, Amnesty claimed that the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances made its first ever visit to the country in September 2013, but that key officials refused to meet with them.

Crossing the line

Declan Walsh, an Islamabad-based correspondent for nine years with The Guardian and The New York Times, is among the few reporters who have ever dared to cross that red line and report on the brutality allegedly suffered by the Baloch people at the hands of the Pakistani government.

Two days before Pakistan went to the polls on May 11, 2013, policemen handed Walsh a letter ordering him to leave the country within 72 hours due to his “undesirable activities”.

“The Balochistan story is one of the most difficult to cover in Pakistan,” the Irish journalist told Al Jazeera from his temporary home in London. “The authorities don’t like foreign journalists entering the province unaccompanied and rarely give permission. They say this is for security reasons. But they also don’t want reporters snooping around in an area where so much militant activity is taking place – Taliban, sectarian and nationalist – and where the security agencies either lack control, or have historical ties with some of these groups.”

Yet Walsh was lucky compared to his predecessor. Carlotta Gall, who also worked for the Times, was badly beaten in Balochistan’s capital, Quetta, in 2006 – by men who identified themselves as members of a special branch of the Pakistan police and who accused her of “being in Quetta without permission”.

“One agent punched me twice in the face and head and knocked me to the floor. I was left with bruises on my arms, temple and cheekbone, swelling of my eye and a sprained knee,” Gall told reporters after the incident. Her mobile phone, computer and notebooks were also seized.

‘Self-censorship’

It’s crystal-clear that foreign journalists are not welcome in Balochistan. But what about the local ones?

Ahmed Rashid is a best-selling Pakistani writer and renowned Central Asia commentator who was an activist on behalf of Balochistan in his youth. “You have to consider the precarious conditions under which local reporters are working in Balochistan province,” he told Al Jazeera.

“Many of them do not even receive a salary, and there are several newspapers [and] television [stations] that do not even bother to have a stringer there… Moreover, reporters are threatened from almost every side: the secret services, the Baloch movement, the groups targeting Shias… often we don’t even get to know who is behind an attack.”

Abdul Razzak, a reporter for the Balochi-language Daily Tawar, went missing in March 2013. His body was discovered in Karachi on August 21. Reporters without Borders reported that Razzak’s body was so badly mutilated that it took the family 24 hours to identify it. The Paris-based NGO ranked Pakistan 159th on its World Press Freedom Index, labelling it as “one of the most difficult countries for journalists”.

Rashid cited “self-censorship”, saying some journalists “tend not to report on the issue for sheer survival. And if it’s not in the Pakistani media, it will hardly reach the outside world, as Western media basically relies on Pakistani sources”.

Ignored by world media

Malik Siraj Akbar is a Baloch writer and the editor of the first online newspaper in English on Balochistan’s issues. It’s been banned in Pakistan since 2010. Many of his editorials touch on the dire situation of local reporters, and highlight the hurdles Balochistan faces in being discussed by foreign media.

“The Western media covers the whole Aghanistan-Pakistan region with a special focus on the ‘war on terror’, Islamic fundamentalism and issues of religious terrorism. There is scant realisation that the Baloch nationalist movement is absolutely different from the Taliban movement. In fact, the Baloch movement is the antithesis of the Taliban and Islamic movements,” said Akbar, who today lives in exile in the US.

Akbar added that the Western media often sees the Baloch movement as a “byproduct” of the war in Afghanistan, or treats it as a domestic Pakistani issue.

But since the recent discovery of mass graves in his native province, he is among the many journalists calling on the UN to send a fact-finding mission to investigate. The Asian Human Rights Commission reported that more than 100 bodies have been recovered from the graves.

Pakistani officials, however, deny these claims, arguing that the total number of bodies is only 15. Nevertheless, last Friday, Abdul Qadir Baloch, the minister for states and frontier regions, announced that the government would launch an inquiry into the mass graves.

“It’s outrageous: The mainstream national media has systematically snubbed the story. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have not issued statements,” complained Akbar.

“There is widespread anger among us, the Baloch, and those who believe in human rights, over such brutal acts – as well as over the silence of the Pakistani government authorities and the media. Unfortunately, all this comes as no surprise for us.”

Follow Karlos Zurutuza on Twitter: @karloszurutuza

courtesy: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2014/02/black-hole-media-balochistan-2014238128156825.html