For two years, Mama was unable to get the authorities to provide any information on his son, until November 23, 2011, when he got a phone call telling him that his son’s body had been found in Mand, near the Iranian border, almost 750 kilometres away from where he was abducted.

“His body was badly injured – there were three gunshot wounds, to his chest and head – and he had also been tortured. There were bruises all over his body. His hand was broken, and one of his eyes was badly wounded. His back had been burned with cigarettes. There was still fresh blood on him when we received the body,” said the 72-year-old, clad in traditional Baluch dress as he walked through the town of Mundera on the 104th day of the group’s march.

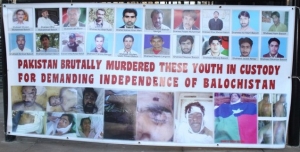

Rekhi’s case is just one of more than 1,000 documented by the Voice of Baloch Missing Persons (VBMP), a rights organisation that has collated information on Baluch missing persons and fights their families’ cases in court since 2009. According to the group, there have been more than 2,825 documented cases of enforced disappearances of Baluch activists since 2005.

And the bodies keep appearing: On January 18, 13 highly decomposed bodies were found in the Tootak area of Balochistan’s Khuzdar district. And on January 31, Nasrullah Baloch, the VBMP’s chairperson, brought the authorities’ attention to another mass grave in Khuzdar that was said to contain more than 100 bodies – some identified as belonging to Baloch pro-independence activists.

‘Propagandistic claims’

The Pakistani government denies that it is responsible for the deaths or the disappearances, and has established a judicial commission to investigate reports of those who have gone missing.

“This is a completely incorrect and propagandistic claim, that there are more than 2,000 people missing,” said a senior official in the provincial home department, speaking on condition of anonymity, when asked about the figures. The official, who deals directly with missing persons’ cases, said that, according to the government and Supreme Court, there were currently only 27 active cases regarding alleged enforced disappearances by the state.

The Commission of Inquiry, meanwhile, a separate judicial body, said it is dealing with 1,475 reported cases of enforced disappearances from all over the country.

Zohra Yusuf, the chairperson of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, says the issue of disappearances is “a core rights issue” and that the situation is “very serious”.

“The issue of missing people is one that despite the attention that the marchers are trying to get, there are continuing cases of disappearances.

The Supreme Court itself has not made much headway in getting people back to their homes – there have been some cases where people have come back – but the number of disappeared is still very high,” she told Al Jazeera, while lauding the efforts of Rekhi and his fellow protesters.

“I think it’s a historic march in the context of Pakistan, because I don’t think anyone has undertaken this form of peaceful protest before, although they have received threats along the way.”

Those threats have been ever-present, according to those marching, and have ranged from daily threatening phone calls to police barricades being set up to prevent the group from marching further; from intimidating security cordons being set up around their nightly encampments to unidentified men cursing at them along their route.

At one point, in the city of Multan, policemen threatened the marchers with force if they did not turn back. “As we were passing by Cantt, we were stopped, and guns were pointed at us – at the women and children, too. We were told be silent. We were very angry. This is shameful, raising a gun at women – how can you then talk about honour? You are disgraceful!”

‘You do not want us’

Farzana Majeed, 28, is one of those women. Her brother, Zakir, was a student activist for the Baluch Students Organisation (Azad), a pro-independence Baluch student group, and was abducted while en route to a friend’s house in rural Balochistan.

That was on June 8, 2009. He remains missing to this day, almost five years later.

“For five years, I have been out on the streets continuously – sometimes outside the Karachi Press Club, sometimes outside Quetta Press Club, sometimes outside the Islamabad Press Club. And now this lengthy, difficult long march from Quetta to Islamabad. But I don’t know why the state here does not understand,” Majeed’s sister said.

“Does the state think that the Baluch insurgency, the freedom struggle – if my brother was a student leader for that, or the other Baluch are activists or leaders – that they can then just pick them and take them away like this, keep them locked up for years?”

Majeed abandoned her pursuit of a masters degree in biochemistry in 2009 to advocate for her brother’s cause. She says that if her brother, and others, are accused of waging an armed campaign against the state, then they should be produced by the state in court and charged with that offence.

“But for the last five years, you have not brought anyone to court. So this means that [the state] does not want to do anything. So this means that you do not want us to be with you. It is completely obvious.”

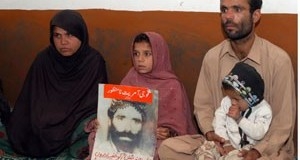

Joining Majeed and Rekhi in their march are 14 others – eight women, three men and three children, including Beauragh Baloch, Jalil Rekhi’s eight-year-old son, who suffers from a congenital heart condition and says he “hates the Pakistani army and ISI” for allegedly abducting his father.

The marchers occasionally raise slogans against the government, or in favour of Baluch rights, but often simply march in silence. As they make their way through Pakistan, they have picked up more marchers and protesters along the way. Some accompanied them for only a few minutes; others joined them for days.

‘The Baluch want freedom’

Mir Muhammad Ali Talpur, originally from the town of Hyderabad, in Sindh, marched with the protesters for 20 days, in two stints.

“Mine is a deep, spiritual involvement in the Baluch national struggle. Now the Baluch want freedom. It’s not about this demand or that demand… it’s now about freedom, the Baluch are fighting for freedom,” said the 68-year-old former fighter with the armed Baluch separatist movement.

Talpur lost his hands in the struggle in 1973, during the first armed battle against the state. “An occupational hazard,” he said of his maimed hands, which were injured while he was preparing explosives.

Balochistan has seen three localised uprisings against the state – in 1948, 1958 and 1963 – with broader armed movements taking place from 1973-77 and from 2005, after the killing of tribal leader Nawab Akbar Bugti.

That fight continues, with armed Baluch groups claiming responsibility for attacks on security forces and government targets that killed at least 274 civilians.

“Now the political and social ethos is defined by the sarmachars and those who are fighting – these two are sarmachars, those who are walking,” he said, using the Baluchi word for an activist who fights for one’s rights regardless of danger.

A message of defiance

For Talpur, who said many of his own fellow fighters have either gone missing or been found dead in the last five years, the marchers’ protest is less about expectation for bringing about change, and more about sending a message of defiance.

“It is about taking the battle to the enemy. And now you just imagine, millions of people… who didn’t know about this, know, because they have seen these people, seen us walking. Millions of people know, everybody that the long march people have come in touch with, there is certainly a definitive change. And you know, that is another thing: This is a message of defiance, defiance of the establishment. [And] defiance is contagious. This is what the establishment is afraid of.”

Mir Muhammad Ali Talpur is a former fighter with the armed Baluch independence movement [Asad Hashim/Al Jazeera]

The message has certainly resonated in parts of the country. In towns and cities in Sindh, where a long-running separatist movement has recently been gaining steam, and southern Punjab, the marchers were given rousing welcomes by crowds ranging from dozens to hundreds of people.

Rekhi and his group have stayed throughout their 104-day journey with friends and well-wishers – being unable to afford staying in hotels, and worried about their own security.

It was in central and northern Punjab, long considered the heartland of Pakistan’s establishment – a term used to describe the military, intelligence services and the state apparatus – that the welcome has been less forthcoming.

Nevertheless, the marchers march on. With just 40km to go to Islamabad, the federal capital, they are preparing to meet with representatives of the UN Human Rights Council and foreign diplomats, they said.

“We are not going to the rulers, we are going to the United Nations only. We will go to the UN office and do a sit-in there. If we had any hope from the rulers, then we would not have to do this long march,” said Muhammad Zahid, 18, a Baluch student from Dera Ghazi Khan.

It’s a sentiment echoed by all those marching – and by none more so than Farzana Majeed.

“Look, the Pakistani parliament, or the Pakistani government, or the military – if they wanted to do something, they would have done it in these last five years. In the last five years, they would have heard my voice. I have been ignored all this time – now what do they want, that I should spend another five years on these streets? Enough is enough. We want our rights.”

Follow Asad Hashim on Twitter: @AsadHashim

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2014/02/families-missing-baloch-march-justice-2014227101949360898.html